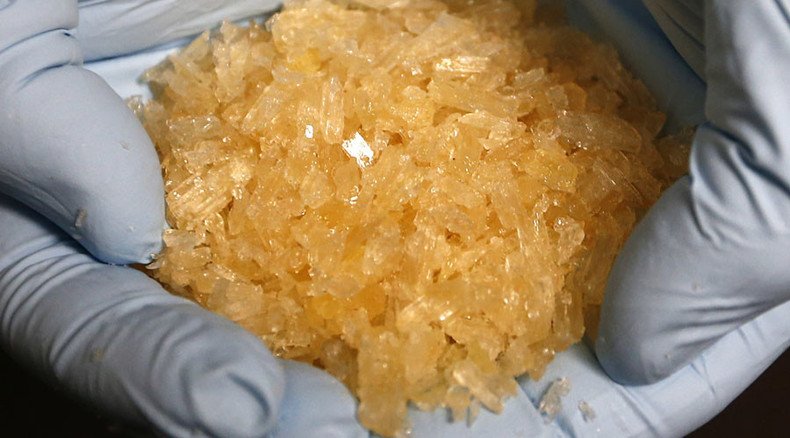

Single injection can erase memories associated with meth use, scientists claim

One dose of an experimental medicine could wipe pleasant memories and associations of a drug high, and make an addict indifferent to temptations, claim US scientists in a groundbreaking piece of research.

“A high rate of relapse is a defining characteristic of substance use disorder for which few treatments are available. Exposure to environmental cues associated with previous drug use can elicit relapse by causing the involuntary retrieval of deeply ingrained associative memories that trigger a strong motivation to seek out drugs,” say authors from the Scripps Research Institute in a paper to be published in the journal Molecular Psychiatry later this month.

“We can disrupt, and potentially erase, drug memories, leaving other memories intact,” says TSRI's Courtney Miller http://t.co/wNswAEnvDv

— Scripps Research (@scrippsresearch) 5 августа 2015“Our lab is focused on identifying and disrupting mechanisms that support these powerful consolidated memories, with the goal of developing therapeutics. We now have a viable target and by blocking that target, we can disrupt, and potentially erase, drug memories, leaving other memories intact,” said Professor Courtney Miller, a key author of the study.

The research is a follow-up to an unexpected discovery two years ago. In 2013, scientists from the leading Florida-based lab realized that if they blocked actin, a chemical used in creating memories, methamphetamine-addicted rats would lose all interest in the drug. The researchers say that the rodents retained interest in food, and all other normal behaviors, and from this deduced that other parts of their memories and cognitive functions were unaffected by the radical treatment.

There was one problem: Actin is a key protein used in many bodily functions, and impairing its work, even for a short time, would be fatal.

Now, the same lab appears to have found a solution – blebbistatin, a drug that hampers actin function in just the brain, without affecting the rest of the body. Furthermore, a single ordinary injection of the medicine, prevented the test rats from relapsing into their addiction for a whole month.

“Drugs targeting actin usually have to be delivered directly into the brain. But blebbistatin reaches the brain even when injected into the body’s periphery and, importantly, the animals remained healthy,” added Ashley M. Blouin, one of the members of the lab team.

READ MORE: Revolutionary way to ‘switch off’ pain discovered

While, if effective, the treatment would represent a revolution in drug addiction, there are many unknowns, and potential ethical quandaries.

The authors themselves admit they do not understand what exactly makes the drug memories different to others, though they speculate there may be a connection to dopamine, a chemical delivered into the brain when we feel pleasure, and a sense of reward.

If this is the case, tampering with those mechanisms not in rats, but in humans could produce much more wide-ranging effects than simply curing them of drug addiction, and could fundamentally alter the psyche of a human subjected to the injections.

READ MORE: Heroin vaccine could help users quit, eliminate overdose risk

But the team at Scripps, which counts several Nobel Prize winners among its faculty, is optimistic about its innovation.

“The hope is that, when combined with traditional rehabilitation and abstinence therapies, we can reduce or eliminate relapse for meth users after a single treatment by taking away the power of an individual’s triggers,” said Miller.

Professor Miller earlier said the team’s research opens the path to tackling other harmful associative memories and environmental cue responses, such as those experienced by smokers, and sufferers of post-traumatic stress disorder.