Dwarf galaxy caused gas ripples in the Milky Way, astronomers say

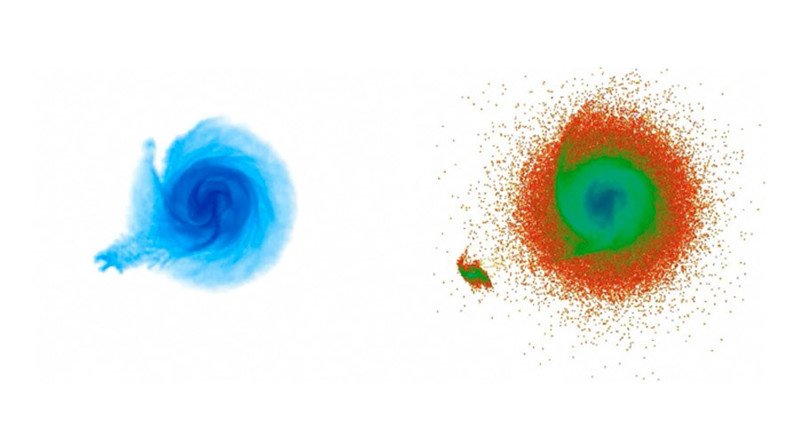

Astronomers may have finally discovered the cause of ripples in gas at the outer disk of our galaxy: a dwarf galaxy, containing dark, unseen material that skimmed the outskirts of our galaxy several hundred million years ago.

“It’s a bit like throwing a stone into a pond and making ripples,” Sukanya Chakrabarti of the Rochester Institute of Technology, who led the research, told a press conference at the American Astronomical Society meeting in Kissimmee, Florida.

“Of course we aren’t talking about a pond, but our galaxy, which is tens of thousands of light years across, and made of stars and gas, but the result is the same – ripples!”

The breakthrough discovery is part of a new discipline called galactoseismology.

“This is really the first non-theoretical application of this field, where we can infer things about the unseen composition of galaxies from analyzing galactic-quakes,” Chakrabarti said.

The research team kept close tabs on a trio of stars, called Cepheid variables. They pulsate radially and are part of the likely dwarf galaxy estimated to lie some 300,000 light years from our galaxy in the direction of the Norma constellation.

“We have a pretty good idea of the distance to these stars because the intrinsic brightness of Cepheid variable stars depends on their period of pulsation, which we can measure,” Chakrabarti noted.

“What I wanted to know was how fast this speeding bullet was going when it passed by our galaxy – with that information we can begin to understand the dynamics, and ultimately how much unseen dark matter is there,” she added.

The team used spectroscopic observations obtained at the Gemini Observatory, which consists of twin 8.1-meter diameter optical/infrared telescopes, located at two of the best observing sites on the planet: mountains in Hawaii and Chile. The observatory's telescopes can collectively access the entire sky.

The researchers found the stars are all speeding away at similar velocities – about 450,000 mph (200 kilometers a second).

“This really implicates these stars as being part of an organized, fast-moving system, which we believe is a dwarf galaxy. It’s also very likely that this dwarf satellite brushed our galaxy millions of years ago and left ripples in its wake,” Chakrabarti said.

“This new, potentially powerful way to study how stars, gas and dust are distributed in galaxies is really quite exciting,” Chris Davis, program director at the US National Science Foundation, said in a press release.

"Known as galactoseismology, it can trace both visible and invisible materials, including the elusive dark matter. It’s a great way to better understand how galaxies and neighboring satellite dwarf galaxies interact as well," he said.

The team will continue their research by looking for more Cepheid variable stars in our galaxy’s halo.

“There could be a population of yet undiscovered Cepheid variables that formed from a gas-rich dwarf galaxy falling into our galaxy’s halo,” Chakrabarti said.

“With the capabilities of today’s telescopes and instruments we should be able to sample enough of the Milky Way’s halo to make reasonable estimates on dark matter content - one of the greatest mysteries in astronomy today!”