Robots threaten 2/3 jobs in developing world, could save first-world economies – UN

Donald Trump could realize his dream of bringing manufacturing jobs back to America if the country adopts the latest innovations in robotics. Yet the impact of “reshoring” on low-skill jobs in certain developing countries could be disastrous, the UN warned.

Citing World Bank data, a brief from the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) claims that up to two-thirds of all jobs in the developing world could be replaced by automation, which is becoming increasingly prevalent in car-making and electronics.

“The increased use of robots in developed countries risks eroding the traditional labor cost advantage of developing countries. If robots are considered a form of capital that is a close substitute for low-skilled workers, then their growing use reduces the share of human labor in total production costs,” says the brief from the UN organization.

The report claims that this could “reignite industrialization” in countries that do not have a pool of cheap, efficient, low-skilled labor, particularly states in South America and Africa, where “employment and output shrinking long before they have attained income levels comparable to those in the developed world ,” after they were outperformed by Asian economies.

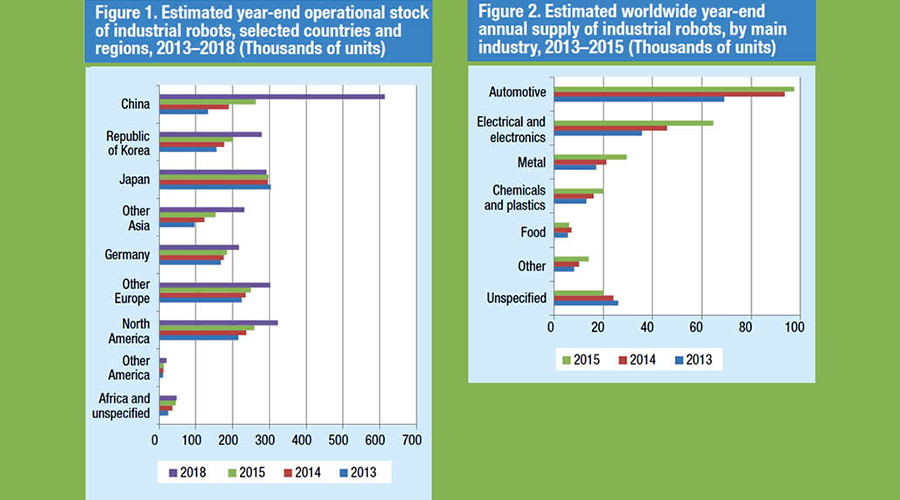

Yet while these plans are hypothetical, China, which powered its way to becoming one of the world’s two biggest economies on the back of cheap labor, is already joining the robot revolution.

“Each year since 2013, China has bought more industrial robots than any other country and, by the end of 2016, is likely to overtake Japan as the world’s biggest operator of industrial robots,” says the brief.“While its robot density – robots per industrial workers – continues to fall short of that of Germany, Japan and the Republic of Korea, the rapid pace of robot deployment is likely to significantly reduce the erosion of China’s comparative advantage in labor-intensive manufacturing.”

The economies of the developed world have less to fear from having their menial work automated – “many of these jobs have already disappeared,” says the report – and more to gain.

“Developed countries may aim to reshore in order to regain international competitiveness in manufacturing and stem the decline in manufacturing employment and the polarization of income that is to the detriment of middle class workers. Reshoring could turn global value chains on their head,” say the authors.

But the report notes that despite robots already being available for decades, the “economy-wide effects [of reshoring] are minor.”

“The slow pace of reshoring may partly be explained by tepid investment and sluggish aggregate demand more generally. In addition, developed countries now lack the supplier networks that some developing countries have built to complement assembly activities,” states UNCTAD.

Besides – both in the developed and developing world – the very nature of automation, means that while the size of the economy will grow from more efficient robots, there will be “polarization” in how the spoils are distributed.According to UNCTAD, the “benefits [will be] accruing in productivity growth and for better-skilled workers and the owners of robots, while low-skilled workers risk being impoverished.”

In the end, the UN suggests that the future adoption of robotics around the world, “final outcomes will be shaped by policies,” but proposes a tax on robots to smooth any transitions.

“Clearly, without the introduction of a major tax on robots as capital equipment, robot-based manufacturing cannot boost the fiscal revenues needed to finance both social transfers, to support workers made redundant by robots, and minimum wages, to stem a decline in the living standards of low-skilled and medium-skilled workers,” say the authors.

For countries left behind, and workers worrying about redundancies, there is one note of reassurance – textile sweatshops.

“Robots are not yet suitable for a range of labor-intensive industries, leaving the door open for developing countries to enter industrialization processes along traditional lines. Garment-making has been a stepping stone in many cases of industrialization,” says UNCTAD.