‘Rainbow’ on Venus captured by ESA

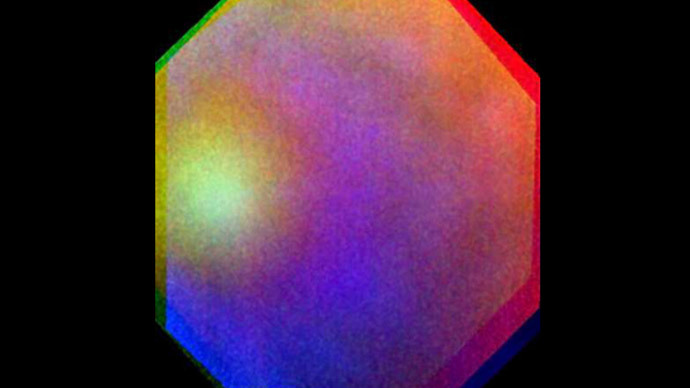

A beautiful ‘rainbow’ like feature, known as a ‘glory’, has been captured by the European Space Agency in the atmosphere of Venus.

“A full glory has never been seen before outside of the terrestrial environment,” Wojciech Markiewicz at the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research in Gottingen, Germany, told New Scientist. Markiewicz was part of the team that spotted the glory.

Glories are considerably smaller than rainbows, but more ‘concentrated’ and are comprised of a series of concentric rings with their own bright ‘core’.

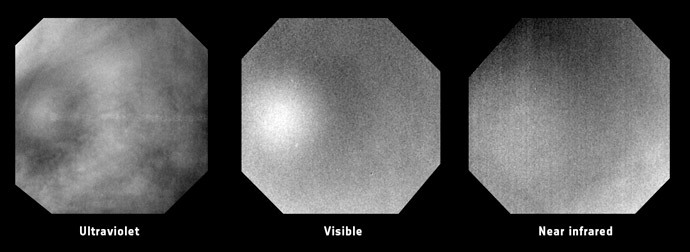

Both rainbows and glories are formed through sunlight being refracted through the droplets that make up clouds. However, for a glory to be formed, the cloud particles must be spherical – and therefore most likely liquid – and all must be of a comparable size.

Glories can only be viewed when their observer is located between the sun and the particles refracting the light. They have been known to appear to people who are flying in planes, or to mountaineers gazing downwards through fog.

In 2011 Markiewicz and his team began the hunt for glories, and discovered what they were looking for on July 24 the same year. The glory they found from 6,000km away was 1,200 km wide. Because of Venus’ dense atmosphere, it is thought that the droplets in this particular case are made out of sulphuric acid, rather than water as they would be on earth.

While Markiewicz and his team were aware of the sulphuric acid clouds, known since the 1920s to shroud Venus, they are still trying to resolve the mysterious ‘other’ component absorbing ultraviolet light, from which they inferred that the planet’s atmosphere is more diverse than previously thought.

“This could be the so-called unknown absorber that people had been trying to identify for years,” Markiewicz told the magazine.

“Even such bizarre things as bacteria were proposed, but no one really knows what it is,” he said.