Life for demolition

Just 40 minutes by train outside of Moscow, dozens of people are living in houses which have been scheduled for demolition for decades. RT’s Anna Bogdanova has a look at their situation and its potential outcome.

Elena and I are walking next to the pink fence of the Podolsk battery factory. Adorned with barbed wire, the fence stretches from one side of the long road to the other. It’s 3 p.m. on a Saturday, yet the street is almost completely empty.

According to what Elena tells me, the battery factory’s facilities take up all the space on each side of the road. The only signs of civilizations are the scarce industrial vehicles, a shop by a gas station, a dry cleaner’s and a traditional Russian banya (public bath). That is the area in which Elena bought a flat three years ago. Her flat is located in one of the buildings which have been scheduled for demolition for nearly thirty years.

The Podolsk battery factory is one of the largest ones in Russia, producing over 60 different types of batteries. It provides batteries for almost all car producers in the country. Some local residents point out that the level of pollution in its vicinity should not allow for any residential areas to be closer than at 1.5 kilometers from it. However, the Podolsk administration, when contacted by RT, insisted that the houses are not within the factory’s sanitary zone.

Elena tells me.

The walk from the train station to our destination takes us around the pink fence and by another set of production plants. These are the facilities of the Podolsk homebuilding factory, which stretches for hundreds of metres in each direction, producing cement, building blocks and other construction materials.

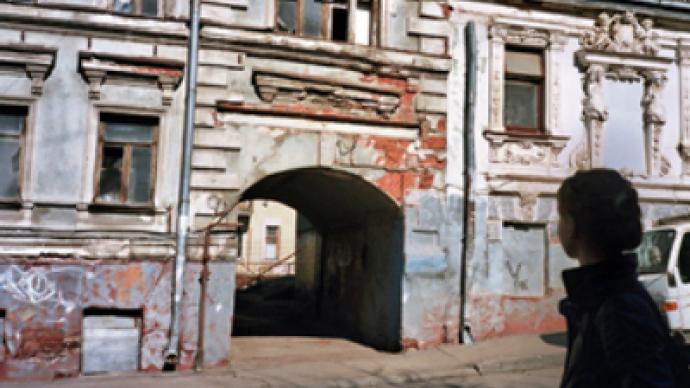

Elena’s flat is located in one of the barrack blocks, which the workers of the homebuilding factory erected in the early 1950’s to use as accommodation. Since then, the buildings have hardly been renovated.

As we approach the barracks, Elena tells me how the ones facing the road have recently been painted over. Her flat is in one of the buildings inside the courtyard and so it has been left as it was – with a simple brick façade.

“When I bought the flat three years ago, the gas heater didn’t work, so I replaced it with an electric one since I could afford it. Not many can do that though, some still live with the gas heater that were installed in the 1950’s and that’s very dangerous,” Elena confesses.

For Elena, buying a flat in such a remote area in the Moscow region was more of a business plan than a living arrangement. When the demolition finally takes place, the local administration promises to provide all of the house’s residents with accommodation equal in size and equidistant to public transport.

Until then, all she can do is wait – and rent her flat out to those looking for cheap accommodation at a manageable distance from Moscow by car. This area of Podolsk, while still being firmly in the city line, is close to a highway which bypasses most traffic jams that usually line the entrance into Moscow.

However, Elena’s situation is an exception rather than a rule. Galina’s family has been living in one of the houses on the estate since the 1960’s. Her husband and her were allocated as workers to the homebuilding factory and provided with free state-owned accommodation. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the family privatised the flat.

Since the houses are now scheduled for demolition, no municipal repairs take place. From time to time, the flat owners take it upon themselves to repaint the doorways or fix the stairways. All this, considering the fact that all of them have to pay council tax which, here in Podolsk, is twice as high as in neighbouring Moscow.

“The only attention we get from our administration is that they collect rubbish once a week. For that at least we are grateful,” Galina tells me.

Both her sons have moved away, but she is determined to see the local administration provide her with a new home, closer to the shops, public transport and easier access to municipal repairs:

“I worked at the homebuilding factory all my life. I always paid the council tax on time. I just don’t understand why they won’t tell us when they will finally demolish everything so that we can at least prepare for it and not wait year after year!”

At night, the last bus stops near the estate at 20:10. Because of this, Galina hardly ever gets any visitors. The walk back to the train station at night is badly lit and too dangerous.

The situation of these residents is, however, nothing out of the ordinary in the Moscow region. Hundreds of homes which were built during the Soviet era are scheduled to be demolished by 2012. Although the government vows to provide accommodation which will suit the residents once the demolition takes place, the situation is not always clear-cut.

Flats are usually registered to a particular owner while they actually serve as a home to more than one family stretching over several generations. Legally, it is often difficult to establish what kind of replacement flat would be appropriate instead of the demolished one.

The Podolsk issue, which both Elena and Galina have become subject to, is unusual in the sense that the residents are not aware of when their homes will be replaced. According to both women, the plan to demolish the barrack-type buildings has been in place for decades.

“This prevents me from doing any repair work around the house,” Galina says. “What’s the point if in a few months it will all be destroyed? Or maybe not. We just don’t know!”

It took RT three days to get in touch with the relevant department of the Podolsk administration as there appeared to be some confusion over who should address the issue of housing upkeep, destined for demolition.

I was first advised to contact the building and architecture commission, who was said to be responsible for the tenders to construct new replacement housing. However, I was soon told that none of the heads were available for commentary and advised to contact another department.

Finally after several days of close liaising with the city’s administration, Valentina Pashaeva, the head of the Podolsk housing and communal services was available for commentary. She gave the administration’s view of the situation and issued an official statement on the subject.

“The law concerning the resettlement of people out of slum dwellings in the Moscow region for the period from 2001 to 2010 was issued by the Moscow region administration. The resolution stipulated for funding from the federal budget, the regional budget, the municipal budget and funds collected from the population as well as private investors,” Pashaeva said.

“The resettlement according to the programme did not happen as swiftly as anticipated because not all the sources of funding were made available. We were working solely based on private investments,” she added.

“As for the houses in question here, they are attached to a renewed version of the legislation issued by the Podolsk city administration, placing them as due for resettlement by 2013-2014. The residents of these houses may want more comfortable accommodation, but I would like to say that they are all centrally heated and we haven’t received any complaints about the state of the houses within the last two years.”

“Last spring the local administration probably decided that it needed to make the area more pretty, so they painted the fence pink,”