License plate reader makers sue Arkansas for banning their tech

Two companies that make automated license plate reader (ALPR) technology have filed a lawsuit against Arkansas, claiming the state’s ban on non-law-enforcement use of ALPRs is a violation of their First Amendment rights.

ALPRs work like high-speed cameras to read, analyze and store images of up to 60 license plates per second, collecting an abundance of driver information, including the date, time and GPS location of a targeted automobile. The two plaintiffs in the lawsuit (as well as in a previous lawsuit against Utah), Digital Recognition Network (DRN) and Vigilant Systems, generate, maintain and share access to databases created by the ALPRs. Law enforcement officials are the companies’ main customers, but private companies like repossession firms and tow truck services want access to the database that contains 1.8 billion records (and growing at a rate of 70 million per month) as well, TechDirt reported.

DRN and Vigilant argue that the dissemination and collection of license-plate data using their technology is constitutionally protected speech because, “At the most basic level, image-content analysis is the extraction of meaningful information from a photograph, and it can be achieved by either a human or by a machine such as a digital camera, mobile phone, computer, processor, or electrical circuit,” the lawsuit said. Basically, they say their technology is no different than any regular Joe taking a picture of a license plate and researching it.

“Taking and distributing a photograph is an act that is fully protected by the first Amendment,” DRN / Vigilant Outside Counsel Michael Carvin said in a statement about the February lawsuit against Utah. “The state of Utah cannot claim that photographing a license plate violates privacy. License plates are public by nature and contain no sensitive or private information. Any citizen of Utah can walk outside and photograph anything they please, including a license plate.”

Regarding the Arkansas suit, Todd Hodnett, DRN’s founder, said to Ars Technica, “The First Amendment lawsuit is focused on ensuring that our free speech rights are protected in the state of Arkansas. We look forward to having our case heard and will not comment further at this time.”

Arkansas’ attorney general defended the state’s law that bans the private collection of ALPR data (but still allows for law enforcement to employ the technology).

“Our law is crafted carefully to protect both the privacy concerns of Arkansans and legitimate law enforcement purposes,” Aaron Sadler, the spokesman for the Arkansas attorney general, told Ars. “We are prepared to defend the law.”

The court will have to weigh the public’s right to privacy against the companies’ right to free speech, which may be no easy feat.

“There's a bit of a disconnect in Viglant's/DRN's logic, but one that's a bit troublesome for the courts to address. By portraying the capture of license plates at a rate of nearly 1,000 per hour as little more than a digital version of someone taking individual photographs of publicly-displayed plates, the companies hope to make its technology look less intrusive than it is,”TechDirt wrote.

“The troublesome part is that courts have held that privacy violations that don't exist in the singular can't magically be summoned by en masse collections. There are definitely privacy concerns, however, especially when this information is used (and misused) by law enforcement.”

One case where the use of ALPR technology went wrong happened to Denise Green in San Francisco in 2009. She was stopped at a red light, when a San Francisco Police Department car pulled up behind her with its lights flashing. She pulled over, then police officers yelled at her, with their guns pointed, to get out of the car with her hands up.

Police believed she was a car thief, based on the information transmitted on their vehicle-mounted license plate reader. However, the license plate number on Green’s Lexus differed by one digit from a truck that had been reported stolen. Officer Alberto Esparza admitted he was unable to see her plate or read the photo his camera captured, calling in to the police dispatch to verify that the number picked up was the same as the stolen vehicle. A judge ruled in May that Green is able to sue the SFPD over the incident.

The American Civil Liberties Union has come out against the use of ALPRs. The ACLU filed Freedom of Information Act requests with police departments and federal agencies that employ the technology, and received 26,000 pages of documents detailing the use and storage of the information received from ALPRs.

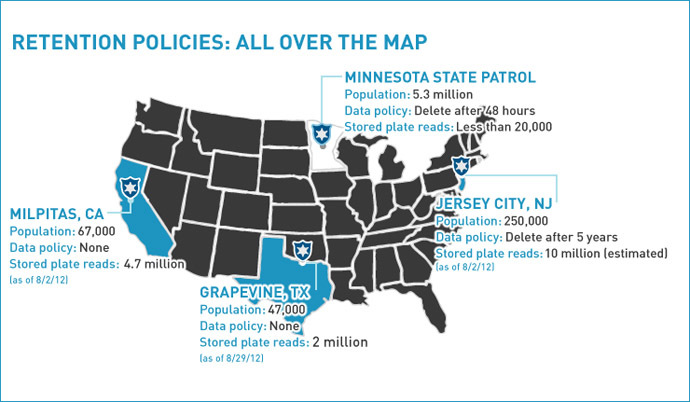

“The documents paint a startling picture of a technology deployed with too few rules that is becoming a tool for mass routine location tracking and surveillance. License plate readers can serve a legitimate law enforcement purpose when they alert police to the location of a car associated with a criminal investigation,” the ACLU wrote. “But such instances account for a tiny fraction of license plate scans, and too many police departments are storing millions of records about innocent drivers.”

The civil liberties advocate details the privacy issues ALPR technology raises:

“Automatic license plate readers have the potential to create permanent records of virtually everywhere any of us has driven, radically transforming the consequences of leaving home to pursue private life, and opening up many opportunities for abuse. The tracking of people’s location constitutes a significant invasion of privacy, which can reveal many things about their lives, such as what friends, doctors, protests, political events, or churches a person may visit.”

However, DRN and Vigilant argue that license plates are not personally identifiable information. “The data that DRN’s ALPR systems collect - a photograph of the license plate, as well as the date time, and location - do not contain any personally identifiable information such as the name, address, or phone number of the registered owner. License-plate data thus cannot be linked to a specifically identifiable person unless it is combined with other data, such as records maintained by a state’s department of motor vehicles,” the lawsuit claims. “Access to such motor-vehicle records is, however, strictly regulated by the federal Drivers Privacy Protection Act… and various state laws.”

TechDirt believes Arkansas will have a high hurdle to leap in proving that it is not discriminating against DRN’s and Vigilant’s right to free speech, and notes that Utah had to heavily amend its law to get the companies to drop the suit. Utah now allows private entities to collect and sell license plate data to other third parties (which government agencies are prohibited from doing), and allows for the companies to hold the information for up to nine months.

Arkansas and privacy advocates may be able to jump that hurdle, though, based on last Wednesday’s 11th Court of Appeals ruling that US law enforcement officials must convince a judge to provide a search warrant before they obtain phone location data from a cell tower.