Russia commemorates victims of Stalin repressions

Russia is marking 70 years since the beginning of the Great Purge, a campaign launched by Stalin against so-called ‘Enemies of the state’ that claimed more than 600,000 lives.

Stalin signed a decree on purges late in July 1937, but it required a couple of days to be forwarded to the local services of the secret police and mass executions across the country began on August 8, so that is why Russia is marking the anniversary today.

The district of Butovo, south of Moscow, is a former execution site in Moscow where a requiem service will be held. This place is sometimes called Russia’s Golgotha in reference to the hill where Jesus Christ was crucified. Many of those executed in Butovo also died for their faith but, unlike Jesus, they didn’t even get a trial.

The compound at Butovo was at that time administered by the secret police and officially it was said to have been used to test new arms and military equipment. But from the very beginning local residents who heard shots and screams of the victims understood that something much grimmer was going on behind the walls.

According to the KGB archives, in less than two years, from August 1937 to October 1938 more than 20,000 people were executed at the site, making it the largest burial place of Stalin repressions’ victims. The youngest prisoner was 13, the oldest was over 80.

“The deadliest time was in February 1937. On one day they shot down 562 people. They were short on executioners so officers who normally did not take part in executions were called in from Moscow. It was like a clean-up day,” Igor Garkavy, director of Butovo Educational Centre, told.

Barbed wire still lines the perimeter of the compound now administered by the Russian Orthodox Church. All around are mounds holding the victims’ bones mixed with litter and uniforms of executioners.

It was a terror, an eradication of the nation’s elite. It was a way to control the society. We’ve seen cases in past history when tyrants were terrorising the elites in order to install their rule. Here this took on a different kind of proportion, because they were building a new history, they were building a new nation. They didn’t need those people for that.

Editor-in-Chief

Russian Profile magazine

Unfortunately, there are many places like this across the country and similar services will be held at them today.

And while the KGB archives have been declassified, the main question still remains ‘Why’? Why did Stalin and his henchmen kill so many of their citizens?

“In July 1937, the Soviet Union was preparing to hold general elections for the Supreme Council. If everybody was to take part, parts of society could have voted against the candidates proposed by the communist party. That was the main reason for the purge – to clean up the society,” Vladimir Buldakov, historian, commented.

The church located at the site of executions in the district of Butovo was built especially to remember the victims of the repressions who died there. It was consecrated just a couple of months ago.

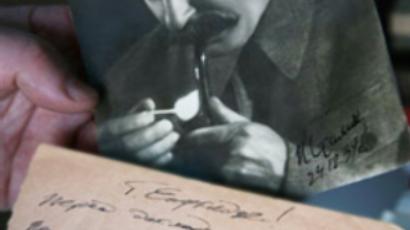

To commemorate this tragic anniversary, the Russian Orthodox Church over the past few weeks has taken a unique journey bringing a large wooden cross from one of the labour camps in the North to the district of Butovo. The 12-metre cross has travelled more than a thousand kilometres, from prisons in the North to a firing range near Moscow, the route from slave labour to death.

“Everywhere we stopped we heard stories of those who died. Locals told us that slopes of man-made canals were covered with concrete to prevent bones washing away,” Reverend Kirill Kaleda said.

For Reverend Kirill, this journey has become a pilgrimage to his roots. His grandfather, also a priest, was arrested in 1937. Only a few years ago the family found out he was executed near Moscow together with hundreds of other clerics.