Band of terrorists: Jazz family that hijacked plane to escape USSR

Twenty-five years after Seven Simeons, a Soviet family jazz band, caused a bloodbath following a failed hijacking, they still polarize opinion. To some they are victims of totalitarianism, to others murderers, prepared to kill innocents for material gain.

On March 8, 1988, during a routine flight between Irkutsk and Leningrad, a man holding an instrument case containing a double bass, a sawn-off shotgun and home-made explosive devices passed a note to the flight attendant, whom he would shoot at point blank range an hour later. It read “Change course to London. Don’t descend, or we will blow up the plane. You are now under our command.”

Next to him sat his accomplices, his nine year-old brother Sergey, eight other siblings, and the beloved mother of the family, who they would have to kill later that day.

Surviving at all costs

From the 1950s until the collapse of the USSR in 1991, hijackers tried to take control of more than sixty Soviet planes. The captors’ demands were always the same: to re-direct the plane to a country beyond the Iron Curtain.

To escape the Soviet Union, the hijackers risked the lives of others, and almost always their own. Few lived to lay their eyes on their desired destination: many were shot before without setting their foot off the plane ever again, others executed after a trial, and only a handful escaped.

Among the hijackers were dissident intellectuals, disgruntled officers and even doomed schoolboys. Yet none of them were as unusual as a matriarch and her eleven children, who rose from absolute poverty in Siberia to international fame, only to meet gruesome deaths in an escape plan that was as audacious as it was naive.

Ninelle Ovechkina’s mother was accidentally shot when she was five, and she spent her childhood in an orphanage. She later married, but her husband was an alcoholic, who would fire upon his own sons with a hunting rifle after his day-long binges.

Although private commercial activity was officially prohibited in the Soviet Union, small farm holds like the Ovechkins’ could survive by selling produce at local markets.

As her family grew, and her husband disappeared for weeks at a time, Ninelle became the farmer, and her children the farmhands.

An early documentary about the band shows her brood milking cows and shoveling manure between band practices. All this under the watchful eye of a stern but caring mother, issuing precise instructions.

Ninelle comes across as principled, but kind.

“Evil begets evil. So, I try to never hurt my children,” she says at one point.

Yet her authority in the family was absolute.

“We could not say no to her. It’s not that we were scared, we could not even think of defying her,” says Mikhail, who played the trombone in the band, and was thirteen at the time of the escape.

Dmitry, the father, died in 1984.

“After the death of our father, she had to become both parents in one person,” said one of the children, Tatyana, who was fourteen during the hijacking attempt. “But whatever was going on around us, we were good. We never smoked or drank, never went to discos.”

Neighbors noted that the Ovechkins rarely spoke to outsiders, preferring their own company after school. When one needed a new purchase or faced a major decision, the entire family would gather for counsel.

Siberian Dixieland

The family’s simple life on the outskirts of the industrial city of Irkutsk was changed by a single encounter.

Vladimir Romanenko, a jazz-loving music teacher, spotted the male siblings performing a folk song in an after-school music group.

A thought that seemed both outrageous and logical formed in his head within seconds. These boys would become a family Dixieland group – from Siberia.

Romanenko assigned the group instruments, and taught them to play Louis Armstrong pieces and jazz interpretations of Russian traditionals.

And so “Seven Simeons” - named after a Russian fairy

tale - was born.

Success was instant.

As Gorbachev’s Perestroika made Western culture not only fashionable, but legitimate, a film crew was dispatched to document the phenomenon of the “peasant family jazz band” (as Ovechkina scathingly referred to their portrayal).

Whatever their objections, the family took to the lifestyle, and began to tour Soviet palaces of culture. Once filled with an endless parade of state-sanctioned ensembles, now these stuffy halls framed by heavy velvet curtains, and adorned with Soviet insignia rocked to sounds pioneered in New Orleans. Used to politely applauding at the ends of songs, the crowds barely knew how to react, clapping along to the unfamiliar rhythms, but not daring to get up off their seats.Of the seven boys in the band (the girls were never sent to study music) most of the older brothers were merely competent musicians, but all eyes were on the two youngest children, Mikhail, and Sergey, who wielded a banjo that seemed bigger than they were.

Irkutsk made the national sensation a symbol of the city, and lavished them with Soviet-style privileges. Instead of their homestead, the Ovechkins moved to two large adjacent flats, were given extra food coupons (a regular part of life in the USSR from the mid-80s until its break-up), and the oldest two children were sent to a prestigious music school in Moscow.

But like most Soviet artists, the family was paid the equivalent of less than $5 for filling out concert halls on a nightly basis.

The new flat may have had running water, but among the shortages of foods that weren’t tinned cabbage, keeping animals brought in more money, and better dinners. Once again doing what it takes to survive, Ninelle defied a strict crackdown on alcohol and started selling vodka illegally at the city market during the day, and outside her flat at night.

But the Ovechkins felt they deserved a better life.

An existence where Seven Simeons would perform in front of hundreds, and then return to a flat where there was barely enough food, became humiliating. Frustrated band leader Vasily also quit the musical academy, claiming that classical-minded professors could not teach him anything about jazz, and that his horizons lay far beyond.

A tour to Japan was the turning point.

The surviving brothers later said that they experienced culture shock at seeing neon lighting, supermarket shelves stacked with food that could be bought without coupons, and memorably for them, flowers in toilets.

Seven Simeons were on the verge of taking the well-trodden path of other Soviet defectors, like dancers Rudolf Nureyev and Mikhail Baryshnikov – escaping the minders who followed them at every step of the tour, and asking for asylum in a Western embassy.

But their mother would remain at home, where she would likely face ostracism, questions from secret service agents, and possibly criminal charges for not informing the authorities about the possibility of defection. They would never see her again.

So, they called off a taxi they planned to sneak out in, and boarded the plane home.

Plan unravels

From the 1920s onwards Soviet citizens were not allowed to leave the country freely, and only a tiny fraction travelled each year on official business or cultural tours. The Ovechkins quickly realized that as nationally-known performers they would not be allowed to emigrate, and even asking to do so meant they would never perform outside of a village auditorium again.

A simple plan was born – with everything riding on it.

“Before we did anything else, we agreed – if the hijacking failed, we would commit suicide rather than give themselves up to the police. We would all die together,” says Mikhail.

The Ovechkins bought a hunting rifle off one acquaintance, and asked another to saw it down. A farmer sold them gunpowder, which they stuffed into several primitive home-made explosive devices. Finally, they enlarged their case for the double bass, to make sure that it could not pass through the security scanner.

But they needn’t have worried.

As local celebrities supposedly flying to Leningrad for their next concert, local police did not search their instrument holders at all, as Ninelle, three of her daughters and seven sons boarded the plane.

The family had sold everything they had, and dressed up in new

outfits they bought with the money - the clothes in which the

world's media would greet them as they stepped out of the plane in

London.

However, like many previous hijackers, the Ovechkins' desired destination was a fantasy. The Tupolev-154 they were flying on did not have enough fuel to go further than Scandinavia.

And the authorities wouldn’t even let them get that far.

“Land the plane on the Soviet side Finnish border, and tell them they are in Finland. Falsely promise them that in exchange for the release of the passengers, they will be given safe passage to Helsinki,” said the voice of the security officer on the ground.

The authorities successfully used the same tactic and the same airport during an attempted hijacking five years earlier, but on landing Dmitry noticed Cyrillic writing on a refueling truck as soon as the plane stopped moving.

As a warning, he instantly killed Tamara Zharkaya, the flight attendant who passed the initial note to the pilot, and demanded that the plane take off straight away.

The pilots barricaded themselves in, and still there was no order to get off the ground.

Without air conditioning, temperature and humidity began to rise within the plane. For two hours, the brothers paced up and down, screaming at the passengers not to look at them, peering outside the steamed-up windows, and perhaps slowly realizing their gambit had failed.

Finally, instructions were dispatched from Moscow.

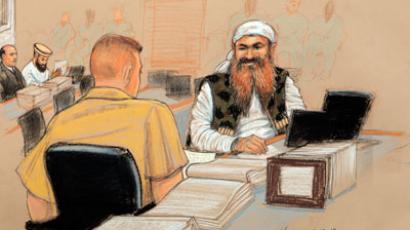

The police unit that burst into the cabin had no special training in hostage rescue. Cowering behind riot shields they sprayed bullets into the aisles, as passengers crouched. One hit Sergey, the youngest of the brothers, in the leg – the others were unharmed. Three passengers were killed, dozens of others wounded.

The brothers realized that they had only minutes before capture.

“They started shouting, ‘Come, let’s blow ourselves up,” Igor, one of the surviving siblings recalled at the trial.

“I did not go – I did not want to die, because I am young. Then I heard my mother shouting ‘Kill me!’ Vasily, my brother shot at her with the shotgun, and I saw her skull open up.”

Mikhail, who was at his brothers’ side, is still angry just recalling the bloody moment.

“I remember my oldest brother shooting my mother right in front of me. Why did he do that? Why did they make me watch that? I was just a boy.” The four oldest brothers then joined hands and set off the explosive. But it was too weak. Rather than killing them it started a fire that quickly spread to the seats.

Instead, the four took the shotgun and one by one shot themselves, in order of oldest to youngest.

As the fire engulfed the interior, passengers started to jump off the plane. The officers met them with a barrage of baton strikes, after being instructed to “detain escaping terrorists”.

The death toll: one air hostess, Ninelle, the four oldest brothers, three passengers, and fourteen more with serious injuries sustained during the escape.

One man's terrorist

Both at the time of the trial, and now, a quarter of a century later, Russians’ condemnation of the hijacking is determined by their attitude towards the Soviet Union.

9/11 turned the hijacking of passenger planes into a nonpareil crime. Yet, at the time, the Ovechkins were viewed with sympathy, or at least understanding, by some. The question was voiced in the increasingly free media and in an award-winning documentary about the family: what kind of country is the Soviet Union that successful musicians hijack planes to escape it?

Others blamed the authorities for putting hundreds of lives at risk to avoid setting a precedent, and for mishandling the rescue. From this incident onwards, only special operations units have handled emergency situations, though there have still been substantial civilian casualties in other hostage situations.

For many others, no deprivation could justify taking innocent lives. Those who knew them also pointed out that the Ovechkins were not freedom fighters, but simply people determined to become better-off at all costs.

What neither side could condone was the plan itself.

The brothers insisted that they came up with the scheme, and that their mother was not told what was about to happen until she boarded the plane. But that was hard to believe.

The stripped down flats in Irkutsk showed that their inhabitants knew they were not coming back, and in the past all important decisions in the Ovechkin family were handled by Ninelle.

Including the choice to send her own children on a badly-planned escape mission that was always likely to end in death.

Coda

Within two years of the hijacking the Berlin Wall was dismantled, and in less than four the Soviet Union perished, and Russians were free to travel to any place in the world.

But even for those members of the family who survived March 8, 1988, there was nothing on the other side.

Olga (28 at the time) served a prison term for terrorism, worked as a market stall trader and was killed in a drunken row by her boyfriend.

Igor (17) also spent time in prison, then became a drug addict, and was later murdered in a police cell by another detainee.

Ulyana (10) became an alcoholic, then tried to commit suicide by jumping in front of a car, but survives with severe disabilities.

Tatyana (14), and the oldest daughter Lyudmila, the only sibling

not to join the hijacking, still live near Irkutsk, while Sergey

the banjo-playing youngster, performed in restaurants, and

has lost contact with the rest of his family.

Mikhail, whom we tracked down in a Spanish hospital, initially appeared to be the most successful of the siblings.

The trombonist married, and moved to St. Petersburg , where he played in several respected jazz collectives, before being invited to play in a Dixieland group in Barcelona.

But, due to persistent drinking he was kicked out, saw his marriage collapse, and came to live on the streets.

Alcoholism caused him to develop seizures, during one of which he fell and fractured his skull, causing a severe brain injury.

He has recovered his memory, but half of his face remains paralyzed, and he can no longer play his instrument well.

“I don’t think I have ever come to terms with what happened that day. There is no way to explain why we decided to do what we did. All I want to do is to go back to my home town and start my life all over again,” he says.

Igor Ogorodnev, RT