Police shootings should be tracked by public health sector, according to Harvard initiative

The American public can’t tell for sure how many people die in police shootings each year. Despite the FBI’s new reporting initiative, a group of Harvard researchers now wants to view shootings as a “notifiable condition” – similar to reporting a disease.

Treating the matter as a public health concern will expedite reporting and allow health agencies to register the incidents quicker, much like a case of measles or another infectious disease, scientists say. They outlined their views in a an editorial in the PLoS Medicine journal, explaining how the new public health approach would help do both – track civilians shot by police more rapidly, and improve reporting on police officers killed on duty. And it proposes to do so without involving new legislation or cooperating with local police departments. Instead, the researchers want the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) to handle the statistics on a weekly reporting basis.

The proposal comes after years of wrangling over inadequate data on civilian deaths at the hands of the police.

“Public health is concerned with myriad determinants of population health and health inequities, including determinants that are not solely with the public health system,” author of the proposal and professor of social epidemiology at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Nancy Krieger, explained to Healthline.

One year on from #TamirRice death: Continued outcry, but no arrests [VIDEO] https://t.co/YPiULmIGAf@ManilaChan

— RT America (@RT_America) November 24, 2015The reason an adequate system for police-related deaths has still not taken off, according to the researchers, is that the law enforcement sector continues to be opposed to the data being made public – “a long-standing and well documented resistance.”

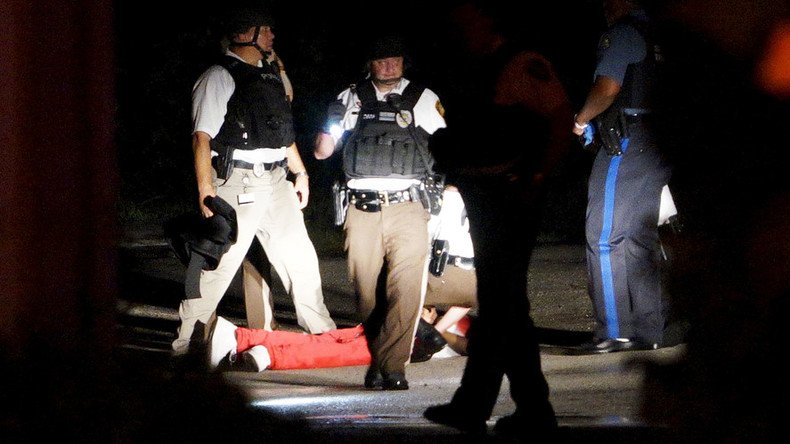

However, the debate has reached new highs of controversy since Michael Brown’s shooting in Ferguson last year, and the topic of unarmed young people being killed by police gained nationwide notoriety.

In 2014, some 14,250 people were shot dead, according to FBI statistics. We also know that 51 percent of law enforcement officers died in the line of duty, and 45 percent by accident. The number of civilians killed by police, however, is not revealed.

According to The Counted, a project operated by the Guardian, an estimated 1,058 people were shot by police in 2015. The number is twice as high for African-Americans as for white people.

“It is unacceptable that the Washington Post and the Guardian newspaper from the UK are becoming the lead source of information about violent encounters between [US] police and civilians. That is not good for anybody,” FBI director James Comey said at a meeting in October.

On Tuesday, the FBI said it would revamp the system for tracking fatal shootings, promising to release data on all such incidents. Stephen L. Morris, assistant director of the FBI’s Criminal Justice Information Services Division, called the current FBI system a “travesty” in an interview to the Washington Post, adding that the new system will be “much more granular.” It would include not only data on all parties involved in the shooting, but also the level of danger faced by the officer, as well as weapons used by both, and other details.

Most importantly, the data will be collected and shared with the public in “near real-time,” as the incidents occur, Morris said, instead of being mentioned only at the end of the year.

For the Harvard researchers behind the public-health-reporting initiative, this is not enough. Police shootings “affect the well-being of the families and communities of the deceased; therefore, law-enforcement-related deaths are public health data, not solely criminal justice data,” they say. The civil unrest created by mass outcries over the shootings, according to the researchers, is disruptive to normal public life, and is therefore also a public health matter.

Furthermore, the number of people killed by police each year is equal to the number of deaths in serious disease outbreaks, the authors write.

“We propose that law-enforcement–related deaths be treated as a notifiable condition, which would allow public health departments to report these data in real-time, at the local as well as national level,” they write.

Talking to Healthline, Krieger also pointed out a shift in public health agencies’ attitudes towards tackling problems once considered to be outside the public health sector. She attributes this to evolving imbalances between different life sectors, which could involve variables such as “poor housing, food policy, low wages, and inadequate transportation systems.”

Although law enforcement’s position on reporting police-related civilian deaths is known, Krieger’s initiative isn’t about “wrongful action by the police,” said Tim Lynch of the Cato Institute’s Project on Criminal Justice, according to Healthline.

Anger & disrespect: Laquan McDonald’s grandmother on shooting video release https://t.co/xWTiZNLiP2pic.twitter.com/2fpiYdiCvD

— RT America (@RT_America) December 2, 2015“When investigations are complete, we will learn whether the incident was justifiable, accidental, or perhaps criminal.”

The group has still not worked out how the mechanics of the system would work, but Krieger proposed to launch public-health reporting as a supplement to existing verification sources, similar to that of the Guardian.