Japanese scientists given green light to modify fertilized human eggs

Japanese scientists have been given the go-ahead to start modifying fertilized human eggs. However, they will not be creating designer babies any time soon, as a government bioethics panel is only allowing the technique for basic research purposes.

The editing of genomes has already been used for plants, human body cells and animals, but there have been debates about the ethics of looking to modify fertilized human eggs.

A Japanese government bioethics panel said on Friday that the scientists will be allowed to use the fertilized human eggs to try and find out which genes play an important role in early phases of growth. The modified eggs will also be used to develop treatments for inherited diseases and to improve technologies related to reproduction, Kyodo news agency reported.

However, the panel said it will not approve the clinical use of modified fertilized human eggs, as the effect on the babies is still unknown.

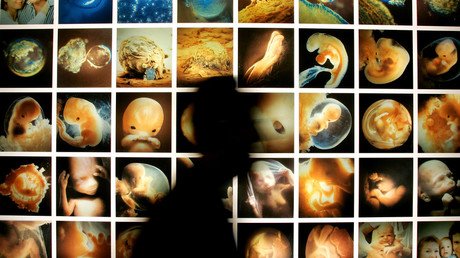

In April 2015, a team of Chinese scientists at the Sun Yat-sen University in Guangzhou created history by successfully editing genomes of human embryos.

The team of scientists used “non-viable” embryos obtained from local fertility clinics, “which were abnormal and could not develop in a baby,” lead researcher Junjiu Huang noted.

George Daley, a stem-cell biologist at Harvard Medical School in Boston, told Nature journal the study was “a landmark,” but warned at expanding the techniques.

In February, a team of British scientists at the Francis Crick Institute in London were given the green light by the Human Fertilization and Embryology Authority (HFEA) to genetically modify human embryos in the first seven days after fertilization.

Scientists hope the research will provide explanations behind what goes wrong in miscarriages and a deeper understanding of the beginnings of human life.

In December, US scientists and activists called for global prohibition on "germline editing," or the genetic modification of human embryos, saying "there is no justification for, and many arguments against" the technology.

"Gene editing may hold some promise for somatic gene therapy (aimed at treating impaired tissues in a fully formed person),” stated a letter from 150 scientists, health practitioners, scholars, and others led by the Center for Genetics and Society (CGS). “However, there is no medical justification for modifying human embryos or gametes in an effort to alter the genes of a future child.”

They said human germline editing could result in miscarriage, stillbirth and serious injury to a mother or child, including afflictions that may not materialize until later in a genetically-modified child's life. In addition, such results of germline modification may quash support for "beneficial uses of genetic technologies" in the future, they said.