Swamp for Trump: Third US President vows to win 16-year Afghan War

Clearly frustrated by the Pentagon’s ineffective strategies, Donald Trump has vowed to fire some of his top generals and aggressively gain ground in Afghanistan. But will the US president be able to prevail in a 16-year war where his two predecessors failed?

Dragging on longer than the Vietnam and Iraq campaigns, Afghanistan is becoming yet another swamp Trump wants to drain in keeping with his colorful election campaign. George W. Bush presided over the two post-9/11 military interventions in Afghanistan and Iraq and Barack Obama promised to end them – but the everlasting Afghan war relentlessly rolls on.

'We are not winning'

During a high-profile situation room meeting in July, Trump reportedly told his national security team it's time for a rapid breakthrough in Afghanistan.

“We are not winning,” he said, as cited in an NBC report. “We are losing.”

Trump, who made headlines after allegedly comparing America's Afghanistan strategy review with renovations of his favorite Manhattan restaurant, appears to be determined to end the sixteen-year Afghan quagmire.

America must go offensive, Trump argued at the meeting, adding, he will not even hesitate to fire General John Nicholson, commander of the US troops in Afghanistan and hire someone who would bring a steadfast, decisive victory.

But the current state of affairs in Afghanistan – dubbed the ‘Graveyard of Empires’ – suggests how different it is from the conflict's portrayal in the media and the very perception of it among the elites in Washington.

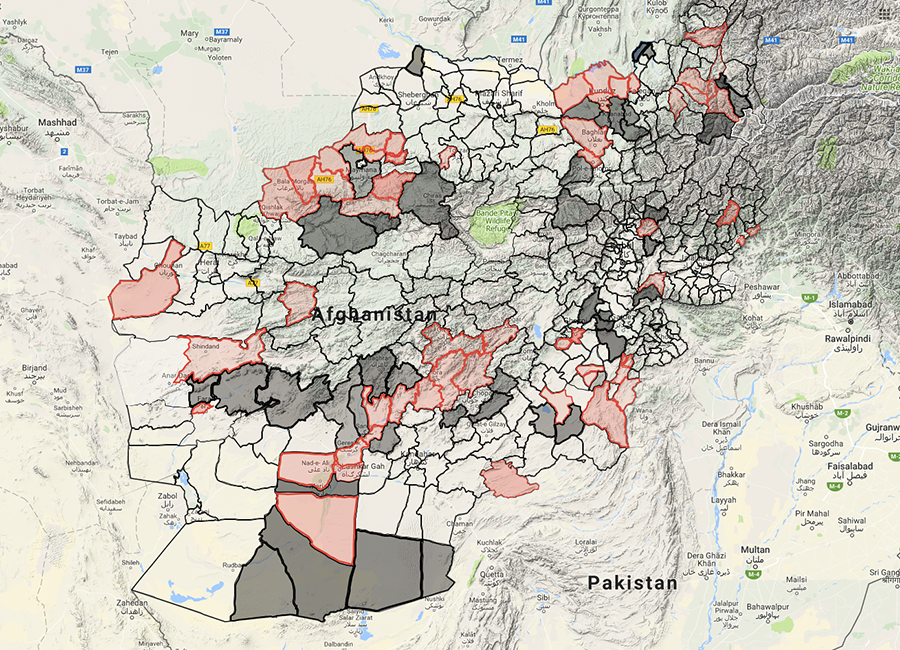

While military leaders are calculating the risks and floating strategies – ranging from raising troop levels to sending a mercenary-manned air force – the Taliban are quietly securing area by area in the lands they want to cleanse of any foreign presence.

In late July, Taliban fighters assaulted and seized the district of Jani Khel in Paktia province lying south of Kabul. The fall of Jani Khel marked the third victory in a row by the Islamists in just four days.

Previously, the Taliban overran Kohistan district in northern Faryab province after storming the district government’s headquarters, forcing local security forces to retreat to another base. Just hours after the seizure of Kohistan, Taliban fighters captured the Taywara district in western Ghor province.

The Taliban’s propaganda wing released an array of photos showing cheering militants next to dead Afghan soldiers as well as US-made Humvees and Ranger pickup trucks. Piles of RPGs, machine guns, rifles, mortars, and other weapons looted from local police arsenals can be seen in the images.

Taliban video details takeover of eastern Afghan district - https://t.co/Ctu10r076Ypic.twitter.com/RFzA4GEfUn

— Long War Journal (@LongWarJournal) 1 августа 2017 г.

In March, the reclusive Taliban delivered yet another bitter blow to Kabul and its Western backers. The town of Sangin in Helmand province, where more than 100 British troops lost their lives, fell to the Taliban after a year-long siege.

Once dubbed the ‘Sangingrad’ – compared to the bloody 1942 Battle of Stalingrad for the ferocity of the fighting – it claimed a quarter of all British fatalities in four years of the entire Afghan campaign, according to the Times.

The province of Helmand has long been the heartland of Afghanistan’s opium cultivation, which is an important gain for the Taliban; and the loss of the Sangin garrison was humiliating for NATO forces, considering the province houses two large NATO-built bases – Camp Bastion, once the largest British overseas military camp built since the Second World War, and Camp Leatherneck, hosting US Marines and British soldiers.

Thousands of lives, billions of dollars

As the Afghan war enters its 17th year, the Trump administration is reportedly expected to send 4,000 additional troops to Afghanistan in the first sizeable deployment since NATO's withdrawal in 2014. The president himself has wondered aloud “why we’ve been there for 17 years,” but his own actions resemble those of his predecessors.

With each year that followed the 2001 invasion, US casualties and civilian deaths rose as steadily as did local drug production. Thousands of British troops were deployed to a make difference on the ground, as were tens of thousands of US troops, at the request of General Stanley McChrystal, following a six-month review of the war plan after President Obama took office. By 2012, the number of US-led coalition troops deployed in Afghanistan reached 130,000 – the size of an average European army.

From being engaged in fierce firefights that lasted days to suicide bombers and IEDs targeting military convoys, the mighty American contingent lost 2,350 soldiers, with 1,846 killed in action, according to the latest Pentagon statistics. But the figure pales in comparison to the number of innocent Afghans killed just in the first half of 2017. Some 1,662 civilians were killed and over 3,500 wounded, according to the mid-year report, by UN Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA).

The US is not likely to ever achieve victory in Afghanistan without involving other regional players, believes former Pentagon official Michael Maloof.

“The military solution itself isn’t going to work. It hasn’t worked before with more troops. It’s not going to work even if he (Trump) orders another 4,000,” he told RT.

According to Maloof, the out-of-the-box approach the US president is looking for may be to “call for a conference of the regional players such as Russia, China, Iran, India – Pakistan, even – and sit down with them and initiate a process whereby we try to look for a political resolution of the crisis.”

“The key is that people who invest an interest in the region, and we certainly all do now because of the threat of terrorism, we all need to be working and talking together,” he added.

The former Pentagon official proposed a “hybrid approach of military and diplomatic initiatives” for Afghanistan.

He reminded that the previous round of peace negotiation in the country broke down after the US announced the withdrawal of its troops and “Taliban said: ‘Well, why should we talk? We should wait for you to leave and do what we want to do.”

“As long as the Taliban realizes that forces in the region are there to stay to ensure the stability of Afghanistan, you can bring them (Taliban) in and talk and see how they can get involved in the government,” Maloof said.

Drugs, bribes & tribes

The US is estimated to have spent over $700 billion on military assistance, reconstruction and economic aid to Afghanistan, but has achieved no significant results. Most of the money was dissolved through the corrupt and criminalized political and military elites as Afghanistan keeps plunging on the Transparency International’s corruption perception index, slumping to 169th on the list in 2016.

In 2013, USAID put its programs in the country on hold after the Afghan health ministry was unable to account for $63 million from the American support package of $236 million.

US troops have also not capped one of the Taliban's major sources of income – drugs. In 2016, illicit opium production grew a whopping 43 percent and reached 4,800 tons, with cultivation areas continuing to grow, according to a report by Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction's estimates.

The booming drug trade provides for 90 percent of the world's illegal opium and has an annual turnover of over $3 billion. A few years ago, Russia's drugs control agency said that as much as a third of Afghan security forces were involved in selling drugs.

With no end in sight to the hostilities, the bloodshed, drug trafficking, poverty and corruption coupled with deep tribal feuds, even in the highest echelons of power, continue to plague the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan. Not even General John Nicholson, the current American commander in charge of the mission, appear to have a clue on when, or if the war will end.

Speaking in Washington in March, General Nicholson insisted that the Afghan campaign was a “stalemate where the equilibrium favors the government.” Carefully avoiding terms like “victory” or “win,” he described his military strategy as “hold-fight-disrupt,” according to the New York Times.

Washington’s approach towards fixing Afghanistan’s seemingly never-ending war has already been portrayed in popular culture. A much-anticipated 2017 Netflix film War Machine, starring Brad Pitt as a fictitious General Glen McMahon, offered a caricatured version of America’s strategy of winning the Afghan war.

“Ah, America,” one of the characters says, with the script sitting well with the current discussions in Washington. “What do you do when the war you're fighting just can't possibly be won in any meaningful sense? Well, obviously, you sack the guy not winning it and you bring in some other guy.”