A millennium of Christianity: What makes Russian Orthodoxy unique?

The faithful in Russia, Ukraine and Belarus are marking 1030 years since their ancestors adopted Christianity – the faith that would ultimately become Orthodoxy, made unique by ten centuries of divergence from Western branches.

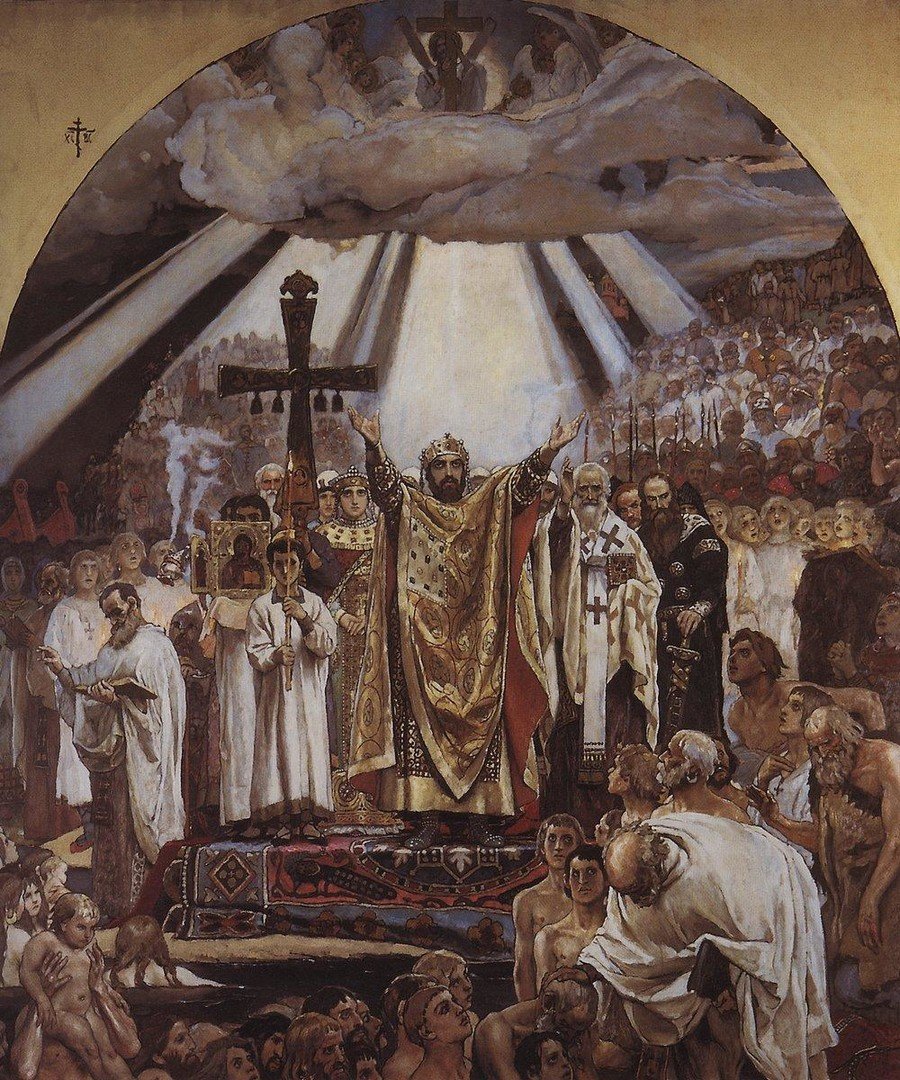

Switching an entire nation’s religion was obviously not a single day’s business – Kievan Rus’, the enormous nation that incorporated parts of modern-day Belarus, Ukraine and Russia, did not simply go to sleep as pagan one day and wake up as Christian the next. 988 was the year that the process started. July 28th was chosen as a commemoration date because it’s the anniversary of St. Vladimir, or Vladimir the Great, the prince who came to power over disparate Slavic tribes and eventually brought them together under the Eastern Christian faith.

As the legend goes, Vladimir was offered a choice between several monotheistic religions: Muslims, Jews, Roman and Byzantine Christians all sent delegations to his court.

Islam, which forbids wine, was rejected – Vladimir said that “drinking was the joy of Rus,” among a number of other fundamental changes the Slavs’ way of life would proceed.

The Jews had no land of their own, a feeble selling point for a ruler who needed religion to tie together vast territories. And the Romans had already had a run-in with Vladimir’s grandmother, Olga of Kiev, the first ruler of Rus’ to be baptized; so he told them that “our forefathers did not accept you.”

The Byzantine priest, on the other hand, intrigued Vladimir, so he sent a mission of his own to Constantinople. The envoys returned dazzled by what they saw in Byzantine churches, saying they could not tell whether it was “heaven or earth.” So the choice was made.

Under the folklore and chroniclers’ sense of it, however, historic facts make the choice even more obvious. Trade ties between Rus’ and Byzantium went back decades before the baptism and Olga of Kiev was baptized in Constantinople, which at the time already had its first divisions with Rome – the cracks that would later split Orthodox and Catholic Christians.

Besides, Byzantium was at the prime of its power and at least partially depended on Vladimir’s military might to keep it that way. The alliance, already mutually beneficial, was now solidified by a common faith.

East vs. West

The differences between Eastern (centered on Constantinople) and Western (with the seat in Rome) Christianity were finalized in the schism of 1054, when Orthodox and Catholic churches officially split. Rus’ followed Byzantium down the Eastern path, coloring it over the years with its own unique flavor.

Both teachings believe in the same God and share the basics of their faiths, but the differences and disputes that caused their split have had them grow into two very diverse phenomena. So what makes the Orthodox faith different?

The Filioque

One of the big splits between East and West is about the origins of the Holy Spirit, part of the Holy Trinity. It revolves, essentially, around the presence or absence of a single word in the 4th-century Nicene Creed, a baseline statement of the Christian faith. That word is “Filioque,” Latin for “and from the Son,” presumably added to the recorded creed in the 6th century.

The Eastern Church rejects the Filioque, thus believing that the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Father alone, as opposed to the Western one, which says it comes from both the Father and the Son, which puts a stronger emphasis on the Son – Jesus.

The Pope

Catholics adhere to papal primacy – the Pope’s "full, supreme, and universal power over the whole Church, a power which he can always exercise unhindered." The Eastern Orthodox Church regards him as "first among equals," without effective power over other churches. Whereas for Catholics, the Pope is the infallible leader of the church, a conduit of divine will, the Orthodox faith holds that the church is guided by the Holy Spirit.

The dogma

Unlike Western denominations, the Orthodox dogma does not hold every human personally complicit in the original sin that got Adam and Eve expelled from Heaven. They do agree that it made humans inherently flawed: Mortal, weak and prone to sin.

Among other things, the Orthodox church rejects the notion of purgatory and holds that the souls of the departed will only attain the end state of bliss or perdition upon Final Judgement.

Celibacy

On a more personal level, the Christian churches are divided on the issue of celibacy: Married men are allowed to become Orthodox priests, but ordained priests are not allowed to marry. Catholic priests are neither allowed to marry nor to have been married before ordination. Other Western denominations, like Protestants or Anglicans, are much more relaxed and place no restriction on priests’ marriage, except in certain specific orders. Mormon priests are even required to be married to advance to the higher ranks.

The rites

Differences here are many and nuanced, and mostly boil down to the interpretation of the meaning of this or that element of a service. For example, Eastern Orthodox churches use leavened bread for the Eucharist, while the Roman rite prescribes using unleavened bread. Catholic services are traditionally performed in Latin, while Orthodox ones use their country’s native tongue. Another example is baptism: In most Catholic churches, the baptized person is sprinkled with water, while Orthodox priests bathe the would-be adherent whole.

The trappings

You will know a Russian Orthodox priest when you see one. The dazzling, flowing golden robes and massive crucifixes worn during liturgy are instantly recognizable. But there’s a more complex symbolism here, as well: In fact, the color of the priests’ cassock, as well as the vestments’ particular make-up depends on the exact nature of the holy day. Rich red and dark crimson, blue, purple, green, golden, white or black are all possible.

The icons

Western Christian images of saints and angels tend to be lifelike, and statues are more common than icons. Not so in the Eastern tradition, whose artists adhere to a distinct style: The icons are two-dimensional, in inverted perspective, every element has meaning and often its size is proportionate to its importance. These rules unite a number of various icon-painting traditions and artists, the most notable of which is Andrei Rublev. The 14th and 15th century artist managed to create eerily lifelike images while in keeping with all the Byzantine guidelines.

The churches

Before the advent of stone temples, and alongside it, wooden churches were built all across Rus’ (later to be Russia). While most were modest and ascetic, some were grand, multi-domed structures worthy of designation as architectural monuments.

When it comes to stone, early Russian churches were built under the supervision of Byzantine architects and followed their style. Soon, though, distinct Russian elements started to bleed through and, eventually, it all condensed into what we see now: Tall structures with many fluted, onion-shaped domes, either golden-plated or colorfully painted, topped by gleaming crucifixes.

Like this story? Share it with a friend!