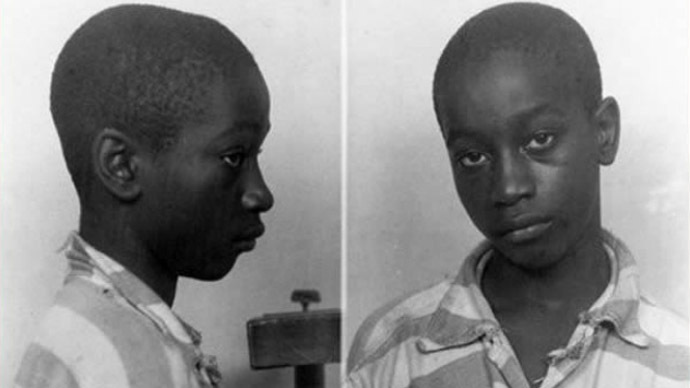

Civil rights activists seek justice for 14-year-old almost 70 years after execution

The youngest American to be executed in the twentieth century may be granted a new trial nearly 70 years after his death because a growing group of supporters, citing new evidence, have pushed for a new trial.

George Stinney was just 14 years old when he was put to death in 1944 for the murder of two young white girls in the segregated town of Alcolu, South Carolina. He was arrested and allegedly confessed to the police, although no record of the conversation exists and police are accused of giving the boy ice cream to coax the confession out of him. Stinney was not read his Miranda rights and his parents were not allowed to see him in jail, according to the Associated Press.

Stinney’s trial lasted just over two hours in part because he was represented by tax commissioner Charles Plowden, who called no witnesses to testify. An all-white jury then deliberated for a mere 10 minutes before declaring Stinney guilty. Just 84 days after the crime the young boy was executed in an electric chair specially designed to fit his small frame.

Plowden’s involvement is especially incriminating because the then 31-year-old had political aspirations and was planning a run for state government. Attorney Steve McKenzie, speaking to Raw Story, said the fact that Plowden needed to remain in the good graces of white voters, combined with his refusal to mount any defense, proved he failed his legal obligation.

“The defense attorney obviously didn’t even know what he was – he wasn’t a criminal lawyer, he was just someone who was appointed,” McKenzie said. “He argued that you couldn’t execute George Stinney because he was 14. Well, the age was 14 for an adult at the time. So, he argued basically the wrong argument in his closing statement.”

The surviving Stinney family now hopes George will be granted a new trial. A motion filed by family attorney Steve McKenzie includes sworn testimony from Stinney’s siblings that they were with him through the whole day when the murder occurred. Filed in Clarendon County, the motion also hopes to find Stinney not guilty posthumously by proving he was not given a fair trial in a racially divided town bent on revenge.

June Binnicker, age 11, and Mary Emma Thames, seven, were found dead on March 25, 1944. They were both brutally stabbed to death with a railroad spike by a person experts now say would have had to be of much larger size than the two victims. A neighbor reported seeing Stinney, who weighed just 90 lbs, playing with the two girls before their disappearance.

Analysts have said the motion for a new trial is largely a symbolic gesture because of a law in South Carolina prohibiting the introduction of new evidence after a trial has concluded.

“I think it’s a long-shot, but I admire the lawyer for trying it,” Kenneth Gaines, a professor at the University of South Carolina law school, told The Guardian. Gaines added that while no hearing has been scheduled, it also has not been thrown out by a judge.

“His family is still thriving, but his soul is not at rest,” said Irene Hill, George’s second cousin. “It has been 69 years now, and there is still no justice. There has been no justice for George, nor for those two young girls, because we know that he is innocent.”

Activists and community members have become increasingly vocal about the case as it has drawn media attention. Whether Stinney’s name will be cleared, though, remains to be seen.

“If we can get the case re-opened, we can go to the judge and say, ‘There wasn’t any reason to convict this child,’” McKenzie said. “There was no evidence to present to the jury. There was no transcript. This case needs to be re-opened. This is an injustice that needs to be righted.”