Online chats, off the record: Cryptocat puts privacy back on the Web

“It’s been suggested to me that what I’m doing might be perhaps dangerous,” recalls Nadim Kobeissi. The 21-year-old, frizzy-haired computer programmer is alert and astute when talking to RT, and he suggests that others should be as well.

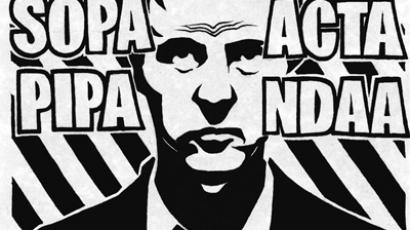

Especially, that is, when using the Internet.Kobeissi seems put off when he’s called a hacker. Since personal computers became more commonplace in households across America, the term “hacker” has been misconstrued by people skeptical of thick-lens-wearing losers huddled over deskchairs, composing and corroborating code for what Hollywood will lead you believe is some sort of sinister plot way beyond the common person’s level of comprehension. Although his frame is scrawny and his his eyes are enlarged by his square-frame glasses, what Kobeissi does sets him apart from that stereotype. What Kobeissi does is something different.“I was always interested in hacking in the sense that it is a practice in which you use computers and digital means to establish tools that may be used for social or political purposes. I was always that and I will remain that,” he says.Kobeissi lives in Canada now but was born in the Middle East where, he says, such resources are now a necessity and without them the Arab Spring may never have taken off to the degree that it did. Soon, however, citizens of the United States might need to have their own arsenal of hacks and workarounds to navigate the Web. That’s where Cryptocat comes into play.Cryptocat is a project that Kobeissi has slaved over throughout 2011, and today he estimates that at least 600 people each day use its services; following a recent write-up in The New York Times, that statistic is expected to skyrocket. On the Internet,“people who want privacy for personal or professional matters” can achieve just that using Cryptocat. It’s the solution for those scared of what sets of eyes might be searching through conversations in the archives of the Internet, as chat records are left to sit on the Web’s biggest servers until an ill-minded hacker or federal agent can break down the door and access the logs, with or without authorization.“A lot of people like to use Facebook chat and Google talk and web IM services like that – and that’s great, but these services actually communicate what you’re talking about to Facebook and Google and there is no privacy. Your communications can easily be intercepted by these parties, and also by governmental organizations,” explains Kobeissi. Privacy concerns pertaining to instant messaging on the Internet might be bigger today than during the dawn of the Information Superhighway. The reason, he says, is an array of laws being considered for approval across North America that might soon put the online activities of any regular Web-surfer under the microscope of their own government.“I come from the Middle East where government surveillance is very well entrenched in the countries there, and I think that there, things like Cryptocat, things also like the Tor project, are much less of a commodity and more of a need,” he tells RT. Cryptocat does the same thing as mainstream chat client.“It tries to establish a similar web IM service that is just as easy to use, but at the same time there is a transparent layer of encryption,” explains its creator.Kobeissi says that his brainchild uses a layer of encryption unmatched by its competition, but it isn’t perfect yet. “We are still trying to make it 1000 percent safe so that it can survive even extremely tough situations — for example, when you’re out on the field somewhere in Iran, trying to evade a government that might do you harm in case they discover what you’re working on.”But in perhaps the worst example of cultural diffusion to devour modern technology, the same trend of trampling on the Internet freedoms of those abroad might soon be coming stateside.“[H]ere also in the West there has been an unfortunate trend where laws like SOPA came close to passing,” he warns. “And now CISPA too, and also in Canada — things like bill c-11 and bill c-50. I think that it’s an unfortunate trend that might be driving away software engineers and even journalists and human rights workers.”The United States Congress is only days away from hearing debates on CISPA, the Cyber Intelligence Sharing and Protection Act drafted by lawmakers as a tool to combat breaches in the nation’s computer infrastructure. Opponents of the act, however, say its censorship-heavy clauses not only replicate the provisions of the failed Stop Online Piracy Act, but are even worse. As with most sequels, SOPA Part II isn’t much to celebrate.Whether or not CISPA is approved will be a matter for Congress and its critics to decide on, but regardless of the outcome, Kobeissi establishes that a trend of online censorship is quickly spreading West. “And so we see things like Cryptocat, things like the Tor project, and other human rights computer software move from the realm of commodity to the realm of need around the world,” he says.“I definitely think that computer human rights technology like this is extremely important,” Kobeissi continues. “I think it provides the infrastructure. It doesn’t provide their will. The Arab Spring happened because there were many Egyptians and Tunisians and people from other counties who were very brave and also very dissatisfied, very grievous, and I think that was the fire that made the Arab Spring possible, but I think that also the human rights computer technology, like hopefully Cryptocat in the future when it's ready to be used in such very dangerous, dangerous situations. I think they provide the infrastructure for those people who are very grievous with their government, to be able to carry out their protestations and civil disobedience more efficiently.”Kobeissi acknowledges that flaws do exist with his project, so to speak. When asked if criminals could always use his service for evil and illicit actions, he says, “I understand that concern and it's been addressed to me before."But just as the US government is trying to crack down on Internet rights by saying the safety of the country is in jeopardy, Kobeissi says pulling the plug on either the Web or his own weapon of choice is never the right idea.“These bad criminal people, terrorists, child pornographers, they’ve existed for thousands of years and you’re not going to resolve the issue by removing the civil rights of the majority of people who do not commit to these actions,” he says. “I don’t think that you’ll be able to solve those problems by restricting the freedoms and the rights of the majority of people and trying to more and more and more to establish this security theatre which gives this vestige of everything being under control while in reality, all you are doing is just invading the privacy of people who just simply want to get a job done or simply want to lead a lifestyle that in which they embrace their typical civil liberties.”Kobeissi says Cryptocat is utilized for around 300 conversations a day right now, each of which can include up to ten chatters clattering away at their keyboards only to have their messages masked through intense encryption. The developer expects that number to soar soon too — he’s at work on platforms for both the Android and iOS operating system for the Apple iPhone.