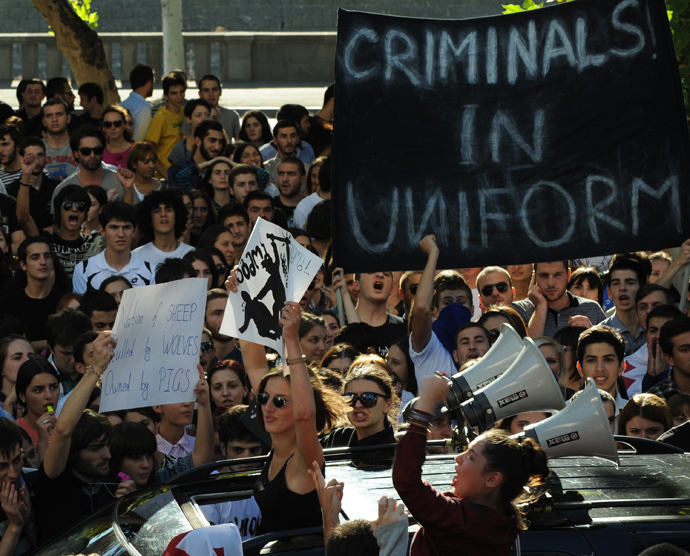

Opposition to Saakashvili ended torture in prisons – Georgian Corrections Minister

Beatings, torture and rape in Georgian prisons, as well as a four-fold increase in the number of inmates, were the dark side of President Saakashvili’s “success story” of a crackdown on crime, the country’s Corrections Minister Sozar Subari told RT.

Multiple instances of torture and abuse in Georgian prisons are

now being investigated, with the country’s former Interior

Minister Vano Merabishvili being put under arrest and a number of

lower-level perpetrators already convicted in court. That only

became possible after President Mikheil Saakashvili’s political

party was defeated at the 2012 parliamentary election by the

party headed by his most powerful opponent, Bidzina Ivanishvili,

who became prime minister.

Many of the violations have been unearthed and exposed by

Saakashvili’s long-time opponent Sozar Subari, who served as the

government’s ombudsman from 2004 to 2009. Under Ivanishvili,

Subari was appointed Corrections Minister in 2012. Speaking to

RT, Subari said that international journalists had

enthusiastically glorified Saakashvili’s “achievements,” while

turning a blind eye to reports of abuse.

Q:How would you explain this practice of torturing

people while boasting about establishing democracy?

A: After the Rose Revolution the punishment for stealing walnuts was 14 years in prison. The number of detainees increased by 400 per cent. Saakashvili called it a tough-on-crime policy. I was the ombudsman at the time, and the only explanation I can give is that the aim of this policy was to intimidate those who had different political views. In addition to the tough-on-crime policy, the prisoners were tortured on a regular basis. It was a logical element of the government policy.

Q:Saakashvili is still in power – isn’t it dangerous

for you to say such things?

A: Saakashvili’s time is over. Regardless, even when he held absolute power and I was the ombudsman, I said exactly the same things about the current government when I was addressing the public or the Parliament or writing my annual reports. Many people were doing the same thing – opposing the regime. If they weren’t, Saakshvili would still be here today, tomorrow, and a good twenty years after that.

Q:Let’s go back to torture practice. How is the

investigation progressing? What did you know of torture practice

as ombudsman?

A: People guilty of practicing torture are currently serving their sentences in Georgia. Their names were stated in the Ombudsman’s reports. One of them is on the run, trying to avoid justice and prosecution. Ombudsman office registered cases when prisoners were locked in solitary confinement cells half-naked for 15-20 days in September, when the outside temperature is pretty low. It was both torture and humiliation.

Q:Are there any guarantees that this won’t happen again? History teaches us that despite being exposed and condemned, some practices are revived after the hype dies down.

About Sozar Subari:

Sozar Subari was elected Ombudsman, or Public Defender, by the Georgian Parliament in 2004. During his five years in office, he became one of the most vocal critics of President Mikheil Saakashvili’s government, accusing him of turning the country into a totalitarian state.

After his appointment as Corrections Minister in October 2012, Georgia’s prison population has decreased by nearly two-thirds – shrinking from over 24,000 to just 9,000.

A: It’s hard to control the actions of any single person,

of course. But there are two guarantees to speak of – close

public scrutiny and the political will of the current government.

Now the main value is the people, human rights, and dignity. If

there was no public pressure in this sphere, if none of these

facts had been exposed, the torture would have gone on even now.

The people were outraged at the previous regime and were fighting

it in any way they could. Bidzina Ivanishvili appearing in the

political arena was the direct result of this outrage. These are

the two factors that played a big role.

Q:How many prisoners are there in Georgia today?

A: Nine thousand.

Q:Are there any political prisoners?

A: Not anymore, but there used to be a lot, probably several hundred. Parliament acquitted 190 political prisoners. There were two laws – one on amnesty of political prisoners and one on mass amnesty regarding nine thousand prisoners. Several thousand people who served half of their sentence and more and didn’t violate any rules were released on parole.

Q:As a rule, states don’t consider those charged with

terrorism political prisoners, but the public often sees them as

such. Do you have prisoners convicted of terrorism?

A: Yes, some.

Q:Like the person accused of an assassination attempt on Mr. Bush?

A: Besides the assassination attempt, he shot a police

officer.

Q:Is your prison system similar to the American

one?

A: What do you mean?

Q:Well, there’s Russian prison system, and a different one in Europe. In American prisons detainees are always under surveillance and control. There are no windows, and they basically live like animals in a zoo.

A: We don’t have a particular system – we just have a bad

one, mainly because our current system is Soviet legacy. About

half of our prisons are old, most of them consist of barracks

housing about three-four hundred prisoners each and a big yard

where a thousand or two prisoners are taken for walks at the same

time. Prison territory takes up to 3-5 ha, and it’s impossible to

control what happens on it all the time. Our first priority is to

humanize the system, so there’s no more torture or beatings, but

better food and medical care, which are now approaching European

standards. The next step is to fight hepatitis C – more than 17

per cent of prisoners have it. The treatment will be free of

charge, of course. We have been battling tuberculosis in prisons

and detention facilities quite successfully by European

standards.

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.