Phobos-Grunt-2: Russia to probe Martian moon by 2022

Russia is set to launch a probe to the Martian moon Phobos by 2022, the head of the Russian Space Research Institute has revealed. The renewal of the ambitious program, which includes taking samples of the moon’s soil, comes despite previous failure.

“We plan to get back to Phobos in 2020-2022,” the

institute’s director, Lev Zeleny, announced on Tuesday, speaking

at the Russian Space Research Institute of the Russian Academy of

Sciences.

The new interplanetary probe mission will become “a

springboard for implementing other similar international

programs,” he added. It is currently codenamed “Boomerang.”

Earlier in April, the scientist said that the mission to the

Martian vicinity will be repeated despite the failure of the

Phobos-Grunt probe in 2011.

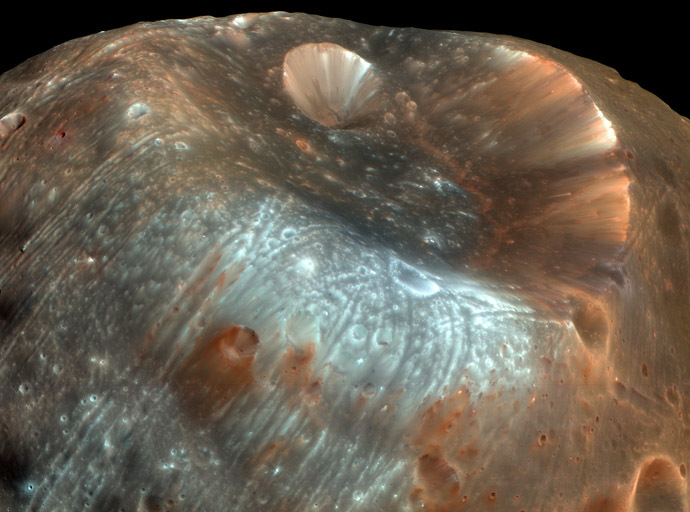

Zeleny explained that the nature and origin of Phobos are of

major interest to science. There is a theory that the moon might

be a captured main-belt asteroid containing materials dating back

to the formation of the solar system.

Other than taking and delivering samples of the Red Planet moon’s

soil for research, which could reveal its origin, the

2011-launched Phobos-Grunt probe had a list of different goals.

Those included the environmental study of the vicinity of Mars,

monitoring of the planet’s atmospheric behavior, search for

traces of life, and a round-trip LIFE experiment involving

capsuled extremophile microbes.

The probe was also tasked with delivering Chinese surveying

satellite “Yinghuo-1” to the orbit of Mars.

However, shortly after takeoff on November 9, 2011, Phobos-Grunt

became trapped in near-Earth orbit after failing to fire its

engines which would have darted it to Mars. Attempts to revive

the probe proved fruitless, as it did not respond to commands

from Earth. The probe eventually plummeted back, partly burning

up in the atmosphere, and its remains fell into the Pacific Ocean

on January 17, 2012.

Later that month, the Russian Space Agency concluded that solar

radiation was behind the malfunction of the probe. The agency’s

ex-director, Vladimir Popovkin, pointed out that the

microelectronic hardware which failed to resist the heavily

charged space particles was foreign-made.

But both the official comments and reports citing agency sources

said that the launch was risky from the start due to poor testing

constrained by deadlines. Consequently, the testing and equipping

of spacecraft developed in Russian space programs was said to be

totally revised and overhauled.

The string of failures of Russia’s attempts to explore Mars and

the larger of its two moons has been dubbed its “Martian curse.”

For the nation that was the first to launch a satellite and a

human being into space and achieved the first unmanned lunar and

Martian soft landings, the setback has been particularly

humiliating.

In the last 25 years, Soviet/Russian scientists carried out four

unsuccessful missions of Phobos-1 and Phobos-2 (1988), Mars-96

(1996) and Phobos-Grunt.

None of the missions were completely in vain, though, as the

technologies developed for them have been used in both Russian

and international Martian projects.

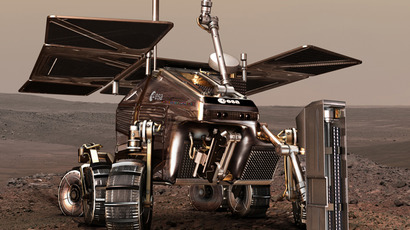

Recently, Roscosmos and the European Space Agency have teamed up

to develop a united ExoMars exploration program. The agencies

plan to send a satellite to Mars in 2016. And in 2018, they plan

to land a rover that would be able to drill the planet’s soil

some 30 times deeper than NASA’s “Curiosity.”

Meanwhile, Russia is slowly but steadily preparing for its most

ambitious space project – the manned interplanetary mission to

Mars.

In 2010 and 2011, Russia carried out the Mars-500 experiment. A

group of six volunteers were locked inside a simulated spacecraft

at the Institute of Biomedical Problems in Moscow for 520 days –

the time it would take to go to Mars and back.

In 2018, Roscosmos plans to stage an even more complicated

experiment by sending two cosmonauts for one year to the

International Space Station (ISS). They will then be returned to

Earth to imitate activities on the Martian surface before

immediately returning to the ISS to simulate the trip back home.

Equally crucial for the manned mission to Mars is the development

of the new nuclear engine with an electric ion propulsion system.

The start of the testing for this drive, which is meant to exceed

the limits of traditional rocket engines, is scheduled for 2017.

Roscosmos has estimated that a functioning atomic engine will not

arrive in space before the year 2025, and said that the next

possible date to send a manned expedition to Mars would occur in

2035.